On December 12, 2020, the world celebrated the five-year anniversary of the signing of the landmark Paris Agreement. While the Trump Administration formally pulled the United States out of Paris, President-elect Joe Biden vowed to rejoin the global pact upon taking office in January 2021, and once again establish the country as a global leader on climate change. In the lead-up to Inauguration Day on January 20, POW is going to re-introduce you to the Paris Agreement, focusing on what it is, its impacts on the Outdoor State, its economic ramifications and what the future holds for the Agreement. We understand that the Paris Agreement is complex, wonky if you will, but we’ve broken it all down to help school you on its most important measures.

Welcome to Paris For Dummies.

The Paris Agreement:

carbon emissions are bad for business

WORDS: DONNY O’NEILL

Paris Agreement Framework

Click below for a refresher on the framework of the Paris Agreement

Opponents of the Paris Agreement have spread enormous amounts of debunked arguments that propagated into an avalanche of misinformation. The biggest speculation being that the systemic changes needed to meet the goals of Paris would simply cost too much. On the contrary, a 2018 study from Stanford University revealed that if the United States failed to achieve the aspirations of Paris, it could cost the economy $6 trillion, and a global failure to meet the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of Paris could lower worldwide gross domestic product (GDP) 25 percent by the end of the century. On the other hand, investing in clean energy and energy-efficient infrastructure could result in a $19 trillion payout, according to a 2017 study by the International Energy Agency and International Renewable Energy Agency. Climate inaction far outweighs the cost of taking action to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2018, Protect Our Winters released its Economic Report, detailing how climate change had rippling ramifications on the winter sports economy in mountain towns across the United States. The report found that winter sports expenditures contributed directly to 121,000 jobs and $8 billion in output to the national economy. Indirectly, winter tourism provided an additional 27,000 jobs and $5.2 billion in economic output. Induced effects of ski industry employee spending resulted in 44,000 jobs and $7.2 billion in economic output. In sum, that’s 191,000 jobs, $6.90 billion in labor income and $20.33 billion in annual economic output.

Pardon our French (this is Paris for Dummies, after all) but that’s a shit ton of dough. And there’s a single evil antagonist that threatens to take the legs out from under the cash cow that is the ski industry: climate change. It’s no secret that skiers ski more when there’s plentiful fresh snowfall. When the snow’s scarce, all but the most diehard snow sliders retreat into the arms of a different pastime. The evidence is there: According to POW’s 2018 Economic Report, during the lowest five snow years between 2001 and 2016, the average decline in skier visits per season was nine percent, 668 jobs were lost each year on average, labor income declined by $620.7 million and the ski industry’s value-added to the economy plummeted by $1.02 billion.

Bottom line: more snow equates to more jobs and money. No snow, rising snow levels and poor quality snow (all induced by climate change) all take away from the tremendous economic impact of the ski industry. Implementing solutions to drastically reduce climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions and meet the milestones of the Paris Agreement will lead to more money in our pockets in the long run, not less.

Aspen Snowmass was a pioneer among ski resorts in recognizing the threat climate change posed to its long-term viability as a business and economic driver in Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley. Representatives of Aspen Skiing Company (ASC) have traveled to Washington D.C. to lobby for climate change. In collaboration with the Aspen Community Foundation, ASC founded The Environment Foundation which funds programs addressing climate change and oil and gas development and works to promote clean-energy development. ASC publishes sustainability reports that transparently track the company’s environmental impacts and efforts to reduce them. Its infused climate-specific messaging in its advertising and urged people to contact local legislators to take action on climate across a multitude of channels. And ASC has made considerable investments in solar energy projects in the Roaring Fork Valley. If these actions sounds familiar, it’s because they all align with meeting the goals outlined by the Paris Agreement (for a refresher on that framework, click here). Tackling climate change is part of Aspen’s business model, and it reflects an industry-wide effort to ensure skiing and snowboarding can continue to be an economic force locally and nationally.

The ski slopes are often the most obvious direction people look when discussing the effects of climate change. Shorter ski seasons and lack of snow can be seen and felt without much effort. But the outdoor recreation economy, as a whole, is no more insulated from the financial impacts of a changing climate than snow sports.

In 2017, the Outdoor Industry Association released its report on the Outdoor Recreation Economy. The report revealed that outdoor recreation was one of the United States’ biggest economic drivers, to the tune of $887 billion in annual consumer spending, 7.6 million jobs, $65.3 billion in federal tax revenue and $59.2 billion in state and local tax revenue. When it came to consumer spending, outdoor recreation accounted for more revenue than the pharmaceutical, motor vehicle, gas and fuel and household utility industries. Outdoor recreation is crucial to rural communities across America, powering economic growth and stability to countless small businesses that benefit from proximity to outdoor access in areas lacking the resources of more populated centers of commerce.

But the effects of climate change threaten all of that. More frequent and volatile forest fires close down national forests. Smoke from these fires inhibits the ability to recreate outside. Rising temperatures disturb cold-water fish populations that anglers depend on. Warming winters prohibit ice formation, deterring ice climbing participation. Hotter summer temperatures urge people to choose air-conditioned living rooms over sprawling trail systems. And less snowfall keeps skiers on the couch and off the slopes. The list goes on.

Systemic changes that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and therefore increase the long term viability of the outdoor recreation industry just make economic sense. Transitioning to clean, renewable energy infrastructure will reduce and eventually eliminate reliance on fossil fuels, the biggest culprit of the country’s emissions. Putting a price on carbon will account for the cost of burning fossil fuels, improving the market for renewables. Electrifying transit will minimize and eventually eliminate emissions from the transportation sector. And blocking oil and gas extraction from public lands, where 20 to 25 percent of the United States’ total emissions stem from, can greatly reduce the country’s contribution to climate change while preserving more area for outdoor recreation and its subsequent economic contributions. And all of these solutions align directly with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The evidence is overwhelming. Reducing global emissions to combat climate change is a better economic strategy than continuing to prop up emissions-based industries—and there’s no better example of the positive financial impacts of a clean energy future than the outdoor recreation industry.

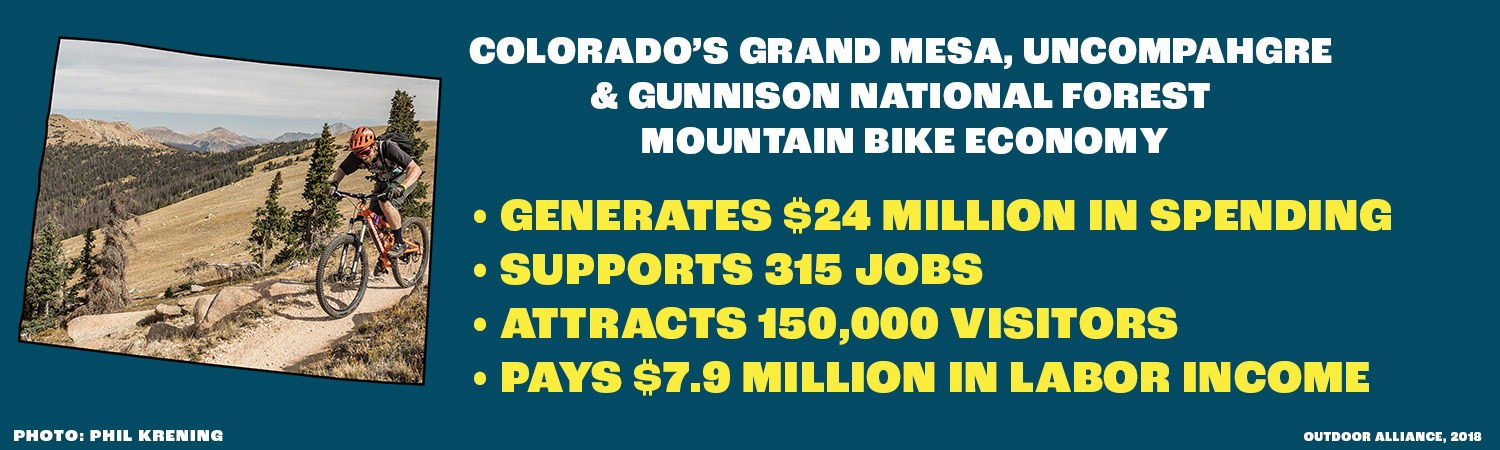

Looking at the outdoor recreation economy can be overwhelming, with big numbers and broad context hitting you left and right. However, the benefits of access to the outdoors and the importance of preserving natural playgrounds are most eye-opening at the local level. To give you a sense of how important the outdoor economy is to states and rural communities in America, we’ve highlighted five places that depend on the present and future viability of outdoor recreation and directly benefit from new policy measures that work toward the goals of Paris.

Local Outdoor Recreation Economies

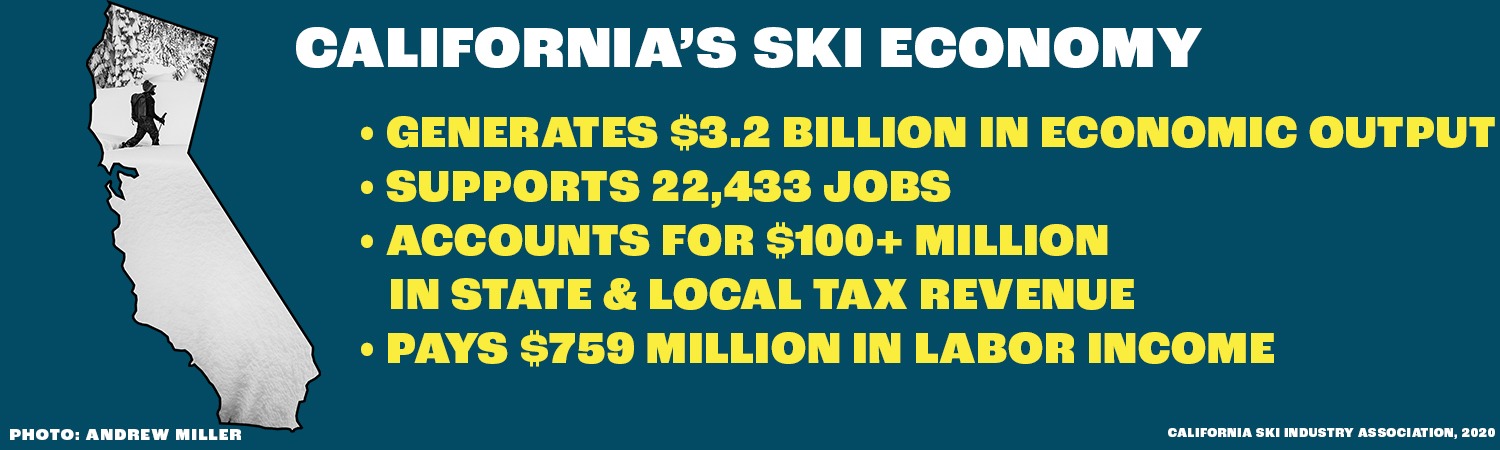

California Outdoor Recreation generates:

- $92.0 billion in annual consumer spending

- 691,000 jobs

- $30.4 billion in wages and salaries

- $6.2 billion in state and local tax revenue

More Californians are employed by the outdoor industry (691,000) than the wine, film and television industries combined (516,000). In reality, California should be known for its access to the outdoors, not for Hollywood or the Napa Valley.

Source: Outdoor Industry Association, 2017

- $28.0 billion in annual consumer spending

- 229,000 jobs

- $9.7 billion in wages and salaries

- $2.0 billion in state and local tax revenue

Colorado has a long history of mining, oil and gas extraction. However, the outdoor industry employs nearly four times as many people (229,000) as those industries combined (58,000).

Source: Outdoor Industry Association, 2017

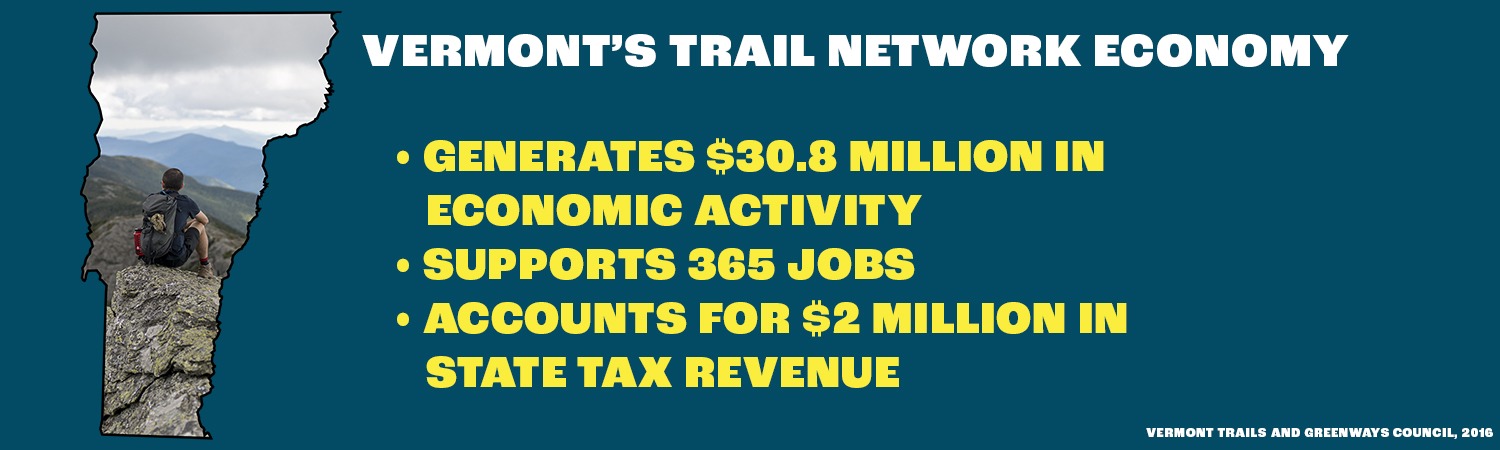

Vermont Outdoor Recreation generates:

- $5.5 billion in annual consumer spending

- 51,000 jobs

- $1.5 billion in wages and salaries

- $505 million in state and local tax revenue

The job of one in seven Vermonters is dependent on outdoor recreation.

Source: Outdoor Industry Association, 2017

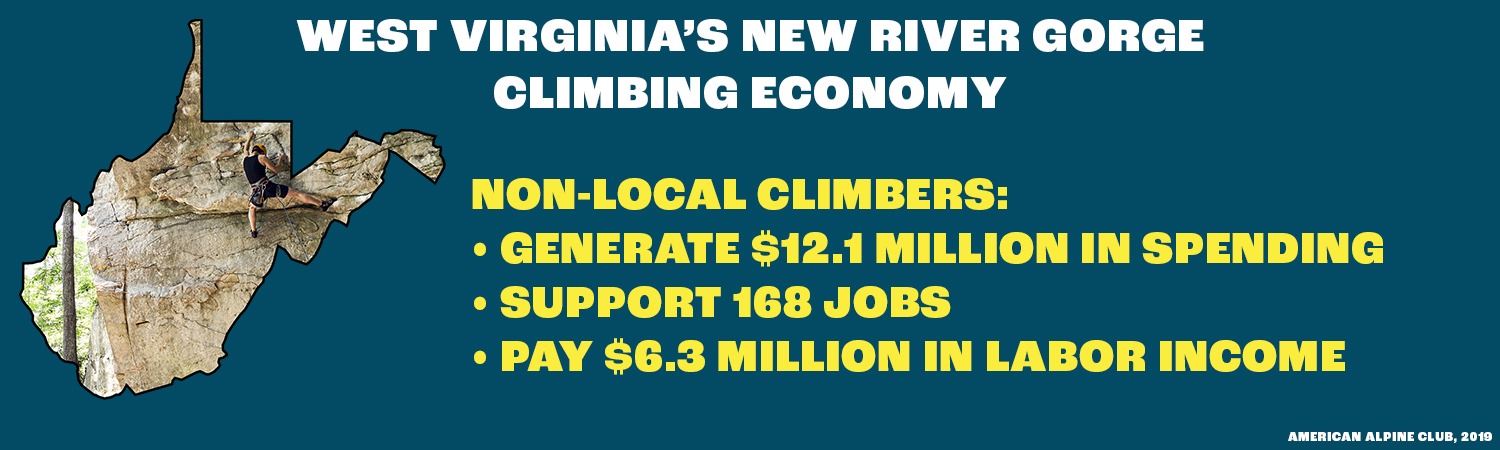

West Virginia Outdoor Recreation generates:

- $9.0 billion in annual consumer spending

- 91,000 jobs

- $2.4 billion in wages and salaries

- $660 million in state and local tax revenue

West Virginia is known for its dependence on coal. However, nearly twice as many West Virginian jobs (91,000) are dependent on the outdoor industry than the coal industry (49,000).

Source: Outdoor Industry Association, 2017

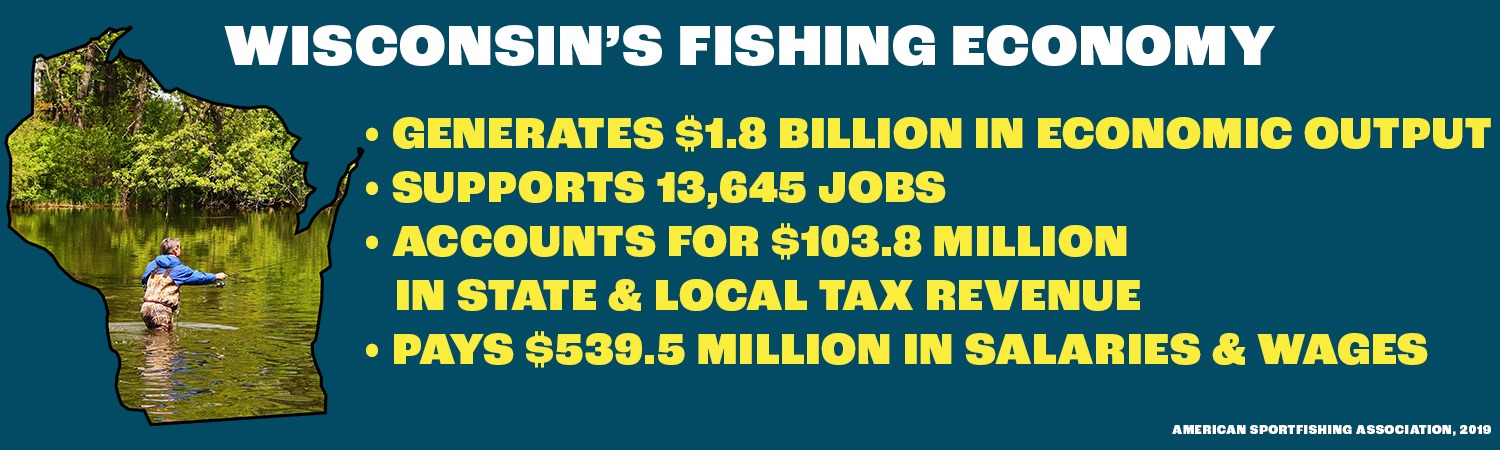

Wisconsin Outdoor Recreation generates:

- $17.9 billion in annual consumer spending

- 168,000 jobs

- $5.1 billion in wages and salaries

- $1.1 billion in state and local tax revenue

Wisconsin is often referred to as America’s Dairyland. When you think of Wisconsin, images of cows, glasses of milk and cheese curds come to mind. But, the amount of jobs directly dependent on outdoor recreation (168,000) is more than double that of the dairy industry (79,000).

In the final installment of our Paris for Dummies series, we’ll dive into what’s next for the Paris Agreement as we progress toward Inauguration Day, 2021.